The Taste Squeeze⚓︎

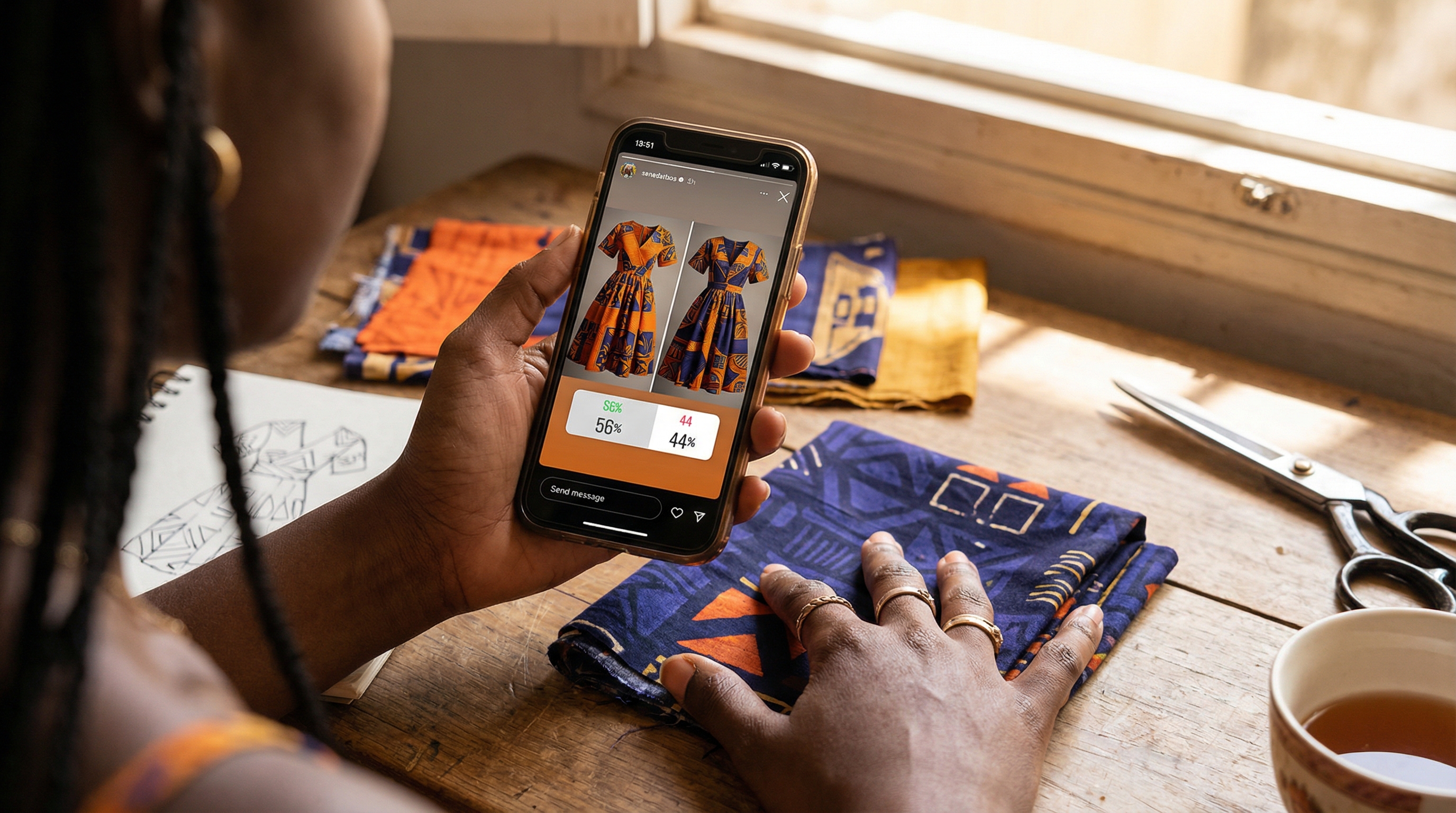

Diarra Bousso runs an AI-first fashion house. She uses generative tools to prototype designs, tests them with Instagram polls before production, and operates an on-demand supply chain that lets her sell garments that don't exist yet—customers pay for AI renders of wool capes, and artisans manufacture them after the order comes in. She's flipped the fashion industry's cash flow equation: instead of spending fourteen months on prototypes, trade shows, and inventory before seeing revenue, she gets paid first.

When asked whether AI will replace designers, her answer is unequivocal: no. The tools amplify human creativity; they don't substitute for it. "You could use all the AI tools in the world," she says, "you will never get these images I just showed you because there's a lot of work behind it that comes from taste, that comes from being a designer, that comes from being an artist, that comes from culture, that comes from my upbringing."

This is the optimistic case for human irreplaceability in creative work, and it deserves to be taken seriously before we complicate it. The argument has three parts, and each contains real insight.

The Iceberg⚓︎

The first part is what I'll call the iceberg argument. When Bousso shows a MidJourney render of a dress, viewers see the tip—the polished image. What they don't see is the twenty steps that preceded it: hand-drawn sketches, proprietary design tools she built herself, years of developing brand DNA, the accumulated knowledge of what her customers respond to. "People just assume you press a button," she says, "but I've probably done like twenty steps before where I had a sketch, I drew something, I used art, I have an app to render it quickly on a sketch-based version, and then I can put it in ChatGPT or MidJourney."

The iceberg argument says that AI handles the visible output while human expertise remains load-bearing beneath the waterline. The person who can prompt MidJourney but lacks the twenty preceding steps produces something fundamentally different from the person who has them. The tool is necessary but not sufficient; the craft persists in what the tool can't see.

Convergence⚓︎

The second part is the convergence argument. If everyone uses the same AI models, the outputs will homogenize. "If you make that really at scale," Bousso observes, "then the whole world is going to be creating a thousand dresses that are going to start being very similar because all these AI models kind of think the same way." What stands out, in a sea of AI-generated adequacy, is the person thinking outside what the models were trained on. Originality becomes the differentiator precisely because the tools commoditize everything else.

Amplification⚓︎

The third part is the amplification argument, captured in a weightlifting metaphor from the conversation: AI can 10x anybody, but would you rather be 10x'd on a 100-pound bench press or a 300-pound one? The person who spent four years in fashion school, who developed taste through thousands of hours of practice, who understands cultural context and material constraints—that person gets amplified more than the novice. AI is a level playing field that paradoxically advantages the already-skilled, because it multiplies existing capability rather than replacing it.

These three arguments form a coherent case. The iceberg means depth persists. Convergence means originality differentiates. Amplification means skill compounds. Taken together, they suggest that human creativity isn't threatened by AI tools but liberated by them—freed from drudgery to focus on what only humans can provide.

The case is persuasive. It's also, I suspect, incomplete.

Pressure from Below⚓︎

During the same conversation, someone raised a counterpoint. What if you don't need taste at all? Release a swarm of AI agents to generate thousands of designs. Seed them across Facebook and Instagram. Let the algorithm surface the handful that resonate. Then manufacture those. You haven't exercised judgment; you've substituted volume and selection pressure for the need to judge.

This is the Shein model, industrialized. Shein reportedly adds thousands of new products daily, tests them with small batches, and scales the winners. The taste happens after the fact, distributed across millions of consumer clicks rather than concentrated in a designer's vision. The iceberg isn't hidden—it's absent. There's no depth beneath the output because depth isn't required. What's required is breadth and iteration speed.

The Shein model inverts Bousso's convergence argument. She says AI outputs will homogenize, so originality differentiates. The brute-force response: so what? If you generate ten thousand variations, statistical variance alone produces outliers. You don't need to think outside what the models were trained on. You need to generate enough volume that the distribution's tails contain winners by chance.

This is pressure from below. At the commodity layer, taste becomes optional. The algorithm does the selecting; the designer becomes unnecessary. The question isn't whether someone with taste can outperform the volume approach—probably yes, at the high end. The question is how much of the market the volume approach can capture before taste becomes relevant. The answer may be: most of it.

Pressure from Above⚓︎

If pressure from below makes taste unnecessary, pressure from above makes it unfalsifiable. This operates on two levels.

The first is "human-made" as premium brand. As AI-generated content floods the market, human involvement becomes a scarcity signal. The EU AI Act's disclosure mandates will accelerate this: once "AI-generated" is flagged, "human-generated" becomes a performable brand. But here's the verification problem. You can prove something touched AI—metadata, detection tools, content credentials. You can't prove it didn't. The premium isn't for verified human origin; it's for the claim of human origin, which may or may not correspond to anything about how the thing was made.

The equilibrium is probably "human-made" as managed ambiguity—like "organic" or "artisanal." A premium category that serves market differentiation without resolving the underlying question of authenticity. Consumers pay for the story; the story's relationship to production becomes optional.

The second level is subtler: taste itself becomes performable. Bousso's iceberg argument assumes that taste is demonstrated through creation—you show your judgment by what you make. But taste can also be demonstrated through curation. The creative director who selects AI outputs and presents them with the right narrative framing, the right aesthetic context, the right cultural positioning—is that person exercising taste, or performing it?

Consider Pharrell Williams as Louis Vuitton's men's creative director. He's a musician, not a trained designer. He doesn't sketch garments. His value is vision and cultural authority—the ability to select and contextualize what others produce. That model predates AI, but AI amplifies it. When anyone can generate a thousand dress options in an afternoon, the scarce skill isn't generation; it's selection. The curator becomes the tastemaker. And curation requires no iceberg. You don't need the twenty steps beneath the render if your role is choosing among renders others produced.

This dissolves the iceberg argument from above. Pressure from below said: you don't need depth, just volume. Pressure from above says: you can perform depth through selection, without having it. The iceberg doesn't need to exist if the appearance of an iceberg is what commands the premium.

The Narrowing Middle⚓︎

Between these pressures, where does taste—actual taste, not performed or bypassed—still function?

The honest answer is: in a narrowing middle. Taste still matters where iteration matters. Bousso can respond when a design doesn't land; she has the underlying capability to adjust, to try again, to diagnose what went wrong. The brute-force approach treats each design as disposable; when conditions change, it just generates more. But some contexts require sustained coherence—a brand identity that evolves without fragmenting, a relationship with buyers who expect continuity, a production pipeline that needs to work on the third version, not just the first.

Taste still matters where verification happens through relationship rather than signal. Bousso's wholesale buyers trust her because they've worked with her, seen her deliver, built a track record. That trust isn't reducible to a "human-made" label; it's accumulated through repeated interaction. In contexts where relationships are the verification mechanism, performed taste gets caught. The buyer who works with you for three seasons knows whether you have depth or not.

Taste still matters where failure is expensive. The $20,000 custom dress designer that Bousso mentions—he can't afford the brute-force approach. Each prototype costs real money; each wrong guess is a cash flow crisis. At the high end, where iteration is costly and mistakes are unrecoverable, judgment still commands a premium because it reduces waste. The question is how narrow that high end becomes.

What Persists⚓︎

Bousso's actual moat isn't taste. It's taste plus operational capability plus relationships. She built an on-demand supply chain that most designers don't have. She trained buyers to accept her model when industry norms said otherwise. She has proprietary tools she developed over years. Taste alone, without these supporting structures, is squeezed from both directions. Taste in context—embedded in systems that make it operational—is harder to replicate precisely because the combination is rarer than any single element.

The $20,000 dress designer has taste but can't execute without cash flow disaster. Shein has execution but no taste, and doesn't need it at the commodity layer. Bousso threads between them: taste that's operationalized, made executable, embedded in relationships that verify it over time.

What survives the taste squeeze isn't taste as an abstract capacity. It's taste-in-context: the judgment that's accumulated through practice, embedded in operational capability, and verified through sustained relationship. The narrowing middle is real, but it's not zero. And in that middle, the people who built the iceberg—who have the twenty steps, the supply chain, the buyer trust—will find that their combination remains difficult to fake, precisely because faking any one element is easy but faking all of them together is hard.

The optimists are right that AI amplifies human creativity. They're wrong if they think taste alone is the moat. The squeeze comes from both directions. Bousso survives it not because she has taste—though she does—but because she built everything else: the on-demand supply chain, the buyer relationships, the tools no one else has. Taste was the starting point. The bundle is the moat. Most people who think they're protected have only the starting point.

Sources⚓︎

- Diarra Bousso, "Beyond the Prompt" podcast interview (December 2024): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hsSGhSeAQK4

- Shein product volume and production model: Business of Apps, McKinsey